WRITTEN AT MOOR-PARK IN JUNE 1689

I

Virtue, the greatest of all monarchies!

Till its first emperor, rebellious man,

Deposed from off his seat,

It fell, and broke with its own weight

Into small states and principalities,

By many a petty lord possess'd,

But ne'er since seated in one single breast.

'Tis you who must this land subdue,

The mighty conquest's left for you,

The conquest and discovery too:

Search out this Utopian ground,

Virtue's Terra Incognita,

Where none ever led the way,

Nor ever since but in descriptions found;

Like the philosopher's stone,

With rules to search it, yet obtain'd by none.

II

We have too long been led astray;

Too long have our misguided souls been taught

With rules from musty morals brought,

'Tis you must put us in the way;

Let us (for shame!) no more be fed

With antique relics of the dead,

The gleanings of philosophy;

Philosophy, the lumber of the schools,

The roguery of alchymy;

And we, the bubbled fools,

Spend all our present life, in hopes of golden rules.

III

But what does our proud ignorance Learning call?

We oddly Plato's paradox make good,

Our knowledge is but mere remembrance all;

Remembrance is our treasure and our food;

Nature's fair table-book, our tender souls,

We scrawl all o'er with old and empty rules,

Stale memorandums of the schools:

For learning's mighty treasures look

Into that deep grave, a book;

Think that she there does all her treasures hide,

And that her troubled ghost still haunts there since she died;

Confine her walks to colleges and schools;

Her priests, her train, and followers, show

As if they all were spectres too!

They purchase knowledge at th'expense

Of common breeding, common sense,

And grow at once scholars and fools;

Affect ill-manner'd pedantry,

Rudeness, ill-nature, incivility,

And, sick with dregs and knowledge grown,

Which greedily they swallow down,

Still cast it up, and nauseate company.

IV

Curst be the wretch! nay, doubly curst!

(If it may lawful be

To curse our greatest enemy,)

Who learn'd himself that heresy first,

(Which since has seized on all the rest,)

That knowledge forfeits all humanity;

Taught us, like Spaniards, to be proud and poor,

And fling our scraps before our door!

Thrice happy you have 'scaped this general pest;

Those mighty epithets, learned, good, and great,

Which we ne'er join'd before, but in romances meet,

We find in you at last united grown.

You cannot be compared to one:

I must, like him that painted Venus' face,

Borrow from every one a grace;

Virgil and Epicurus will not do,

Their courting a retreat like you,

Unless I put in Caesar's learning too:

Your happy frame at once controls

This great triumvirate of souls.

V

Let not old Rome boast Fabius' fate;

He sav'd his country by delays,

But you by peace.[1]

You bought it at a cheaper rate;

Nor has it left the usual bloody scar,

To show it cost its price in war;

War, that mad game the world so loves to play,

And for it does so dearly pay;

For, though with loss, or victory, a while

Fortune the gamesters does beguile,

Yet at the last the box sweeps all away.

VI

Only the laurel got by peace

No thunder e'er can blast:

Th'artillery of the skies

Shoots to the earth and dies:

And ever green and flourishing 'twill last,

Nor dipt in blood, nor widows' tears, nor orphans' cries.

About the head crown'd with these bays,

Like lambent fire, the lightning plays;

Nor, its triumphal cavalcade to grace,

Makes up its solemn train with death;

It melts the sword of war, yet keeps it in the sheath.

VII

The wily shafts of state, those jugglers' tricks,

Which we call deep designs and politics,

(As in a theatre the ignorant fry,

Because the cords escape their eye,

Wonder to see the motions fly,)

Methinks, when you expose the scene,

Down the ill-organ'd engines fall;

Off fly the vizards, and discover all:

How plain I see through the deceit!

How shallow, and how gross, the cheat!

Look where the pulley's tied above!

Great God! (said I) what have I seen!

On what poor engines move

The thoughts of monarchs and designs of states!

What petty motives rule their fates!

How the mouse makes the mighty mountains shake!

The mighty mountain labours with its birth,

Away the frighten'd peasants fly,

Scared at the unheard-of prodigy,

Expect some great gigantic son of earth;

Lo! it appears!

See how they tremble! how they quake!

Out starts the little beast, and mocks their idle fears.

VIII

Then tell, dear favourite Muse!

What serpent's that which still resorts,

Still lurks in palaces and courts?

Take thy unwonted flight,

And on the terrace light.

See where she lies!

See how she rears her head,

And rolls about her dreadful eyes,

To drive all virtue out, or look it dead!

'Twas sure this basilisk sent Temple thence,

And though as some ('tis said) for their defence

Have worn a casement o'er their skin,

So wore he his within,

Made up of virtue and transparent innocence;

And though he oft renew'd the fight,

And almost got priority of sight,

He ne'er could overcome her quite,

In pieces cut, the viper still did reunite;

Till, at last, tired with loss of time and ease,

Resolved to give himself, as well as country, peace.

IX

Sing, beloved Muse! the pleasures of retreat,

And in some untouch'd virgin strain,

Show the delights thy sister Nature yields;

Sing of thy vales, sing of thy woods, sing of thy fields;

Go, publish o'er the plain

How mighty a proselyte you gain!

How noble a reprisal on the great!

How is the Muse luxuriant grown!

Whene'er she takes this flight,

She soars clear out of sight.

These are the paradises of her own:

Thy Pegasus, like an unruly horse,

Though ne'er so gently led,

To the loved pastures where he used to feed,

Runs violent o'er his usual course.

Wake from thy wanton dreams,

Come from thy dear-loved streams,

The crooked paths of wandering Thames.

Fain the fair nymph would stay,

Oft she looks back in vain,

Oft 'gainst her fountain does complain,

And softly steals in many windings down,

As loth to see the hated court and town;

And murmurs as she glides away.

X

In this new happy scene

Are nobler subjects for your learned pen;

Here we expect from you

More than your predecessor Adam knew;

Whatever moves our wonder, or our sport,

Whatever serves for innocent emblems of the court;

How that which we a kernel see,

(Whose well-compacted forms escape the light,

Unpierced by the blunt rays of sight,)

Shall ere long grow into a tree;

Whence takes it its increase, and whence its birth,

Or from the sun, or from the air, or from the earth,

Where all the fruitful atoms lie;

How some go downward to the root,

Some more ambitious upwards fly,

And form the leaves, the branches, and the fruit.

You strove to cultivate a barren court in vain,

Your garden's better worth your nobler pain,

Here mankind fell, and hence must rise again.

XI

Shall I believe a spirit so divine

Was cast in the same mould with mine?

Why then does Nature so unjustly share

Among her elder sons the whole estate,

And all her jewels and her plate?

Poor we! cadets of Heaven, not worth her care,

Take up at best with lumber and the leavings of a fare:

Some she binds 'prentice to the spade,

Some to the drudgery of a trade:

Some she does to Egyptian bondage draw,

Bids us make bricks, yet sends us to look out for straw:

Some she condemns for life to try

To dig the leaden mines of deep philosophy:

Me she has to the Muse's galleys tied:

In vain I strive to cross the spacious main,

In vain I tug and pull the oar;

And when I almost reach the shore,

Straight the Muse turns the helm, and I launch out again:

And yet, to feed my pride,

Whene'er I mourn, stops my complaining breath,

With promise of a mad reversion after death.

XII

Then, Sir, accept this worthless verse,

The tribute of an humble Muse,

'Tis all the portion of my niggard stars;

Nature the hidden spark did at my birth infuse,

And kindled first with indolence and ease;

And since too oft debauch'd by praise,

'Tis now grown an incurable disease:

In vain to quench this foolish fire I try

In wisdom and philosophy:

In vain all wholesome herbs I sow,

Where nought but weeds will grow

Whate'er I plant (like corn on barren earth)

By an equivocal birth,

Seeds, and runs up to poetry.

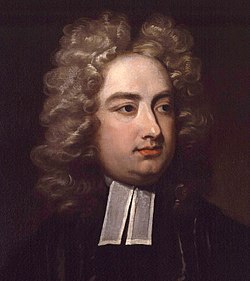

Ode To The Hon. Sir William Temple

Jonathan Swift

(1)

Poem topics: believe, breath, fate, food, god, green, heaven, horse, innocence, june, noble, pain, poetry, pride, sick, sister, son, sun, time, tree, Print This Poem , Rhyme Scheme

Submit Spanish Translation

Submit German Translation

Submit French Translation

Write your comment about Ode To The Hon. Sir William Temple poem by Jonathan Swift

Best Poems of Jonathan Swift