INTRODUCTION.

I sought the long clear twilights of the North,

When, from its nest of trees, my father's house

Sees the Aurora deepen into dawn

Far northward in the East, o'er the hill-top;

And fronts the splendours of the northern West,

Where sunset dies into that ghostly gleam

That round the horizon creepeth all the night

Back to the jubilance of gracious morn.

I found my home in homeliness unchanged;

For love that maketh home, unchangeable,

Received me to the rights of sonship still.

O vaulted summer-heaven, borne on the hills!

Once more thou didst embrace me, whom, a child,

Thy drooping fulness nourished into joy.

Once more the valley, pictured forth with sighs,

Rose on my present vision, and, behold!

In nothing had the dream bemocked the truth:

The waters ran as garrulous as before;

The wild flowers crowded round my welcome feet;

The hills arose and dwelt alone in heaven;

And all had learned new tales against I came.

Once more I trod the well-known fields with him

Whose fatherhood had made me search for God's;

And it was old and new like the wild flowers,

The waters, and the hills, but dearer far.

Once on a day, my cousin Frank and I,

Drove on a seaward road the dear white mare

Which oft had borne me to the lonely hills.

Beside me sat a maiden, on whose face

I had not looked since we were boy and girl;

But the old friendship straightway bloomed anew.

The heavens were sunny, and the earth was green;

The harebells large, and oh! so plentiful;

While butterflies, as blue as they, danced on,

Borne purposeless on pulses of clear joy,

In sportive time to their Aeolian clang.

That day as we talked on without restraint,

Brought near by memories of days that were,

And therefore are for ever--by the joy

Of motion through a warm and shining air,

By the glad sense of freedom and like thoughts,

And by the bond of friendship with the dead,

She told the tale which I would mould anew

To a more lasting form of utterance.

For I had wandered back to childish years;

And asked her if she knew a ruin old,

Whose masonry, descending to the waves,

Faced up the sea-cliff at whose rocky feet

The billows fell and died along the coast.

'Twas one of my child marvels. For, each year,

We turned our backs upon the ripening corn,

And sought the borders of the desert sea.

O joy of waters! mingled with the fear

Of a blind force that knew not what to do,

But spent its strength of waves in lashing aye

The rocks which laughed them into foam and flight.

But oh, the varied riches of that port!

For almost to the beach, but that a wall

Inclosed them, reached the gardens of a lord,

His shady walks, his ancient trees of state;

His river, which, with course indefinite,

Wandered across the sands without the wall,

And lost itself in finding out the sea:

Within, it floated swans, white splendours; lay

Beneath the fairy leap of a wire bridge;

Vanished and reappeared amid the shades,

And led you where the peacock's plumy heaven

Bore azure suns with green and golden rays.

Ah! here the skies showed higher, and the clouds

More summer-gracious, filled with stranger shapes;

And when they rained, it was a golden rain

That sparkled as it fell, an odorous rain.

But there was one dream-spot--my tale must wait

Until I tell the wonder of that spot.

It was a little room, built somehow--how

I do not know--against a steep hill-side,

Whose top was with a circular temple crowned,

Seen from far waves when winds were off the shore--

So that, beclouded, ever in the night

Of a luxuriant ivy, its low door,

Half-filled with rainbow hues of deep-stained glass,

Appeared to open right into the hill.

Never to sesame of mine that door

Yielded that room; but through one undyed pane,

Gazing with reverent curiosity,

I saw a little chamber, round and high,

Which but to see, was to escape the heat,

And bathe in coolness of the eye and brain;

For it was dark and green. Upon one side

A window, unperceived from without,

Blocked up by ivy manifold, whose leaves,

Like crowded heads of gazers, row on row,

Climbed to the top; and all the light that came

Through the thick veil was green, oh, kindest hue!

But in the midst, the wonder of the place,

Against the back-ground of the ivy bossed,

On a low column stood, white, pure, and still,

A woman-form in marble, cold and clear.

I know not what it was; it may have been

A Silence, or an Echo fainter still;

But that form yet, if form it can be called,

So undefined and pale, gleams vision-like

In the lone treasure-chamber of my soul,

Surrounded with its mystic temple dark.

Then came the thought, too joyous to keep joy,

Turning to very sadness for relief:

To sit and dream through long hot summer days,

Shrouded in coolness and sea-murmurings,

Forgot by all till twilight shades grew dark;

And read and read in the Arabian Nights,

Till all the beautiful grew possible;

And then when I had read them every one,

To find behind the door, against the wall,

Old volumes, full of tales, such as in dreams

One finds in bookshops strange, in tortuous streets;

Beside me, over me, soul of the place,

Filling the gloom with calm delirium,

That wondrous woman-statue evermore,

White, radiant; fading, as the darkness grew,

Into a ghostly pallour, that put on,

To staring eyes, a vague and shifting form.

But the old castle on the shattered shore--

Not the green refuge from the summer heat--

Drew forth our talk that day. For, as I said,

I asked her if she knew it. She replied,

"I know it well;" and added instantly:

"A woman used to live, my mother tells,

In one of its low vaults, so near the sea,

That in high tides and northern winds it was

No more a castle-vault, but a sea-cave!"

"I found there," I replied, "a turret stair

Leading from level of the ground above

Down to a vault, whence, through an opening square,

Half window and half loophole, you look forth

Wide o'er the sea; but the dim-sounding waves

Are many feet beneath, and shrunk in size

To a great ripple. I could tell you now

A tale I made about a little girl,

Dark-eyed and pale, with long seaweed-like hair,

Who haunts that room, and, gazing o'er the deep,

Calls it her mother, with a childish glee,

Because she knew no other." "This," said she,

"Was not a child, but woman almost old,

Whose coal-black hair had partly turned to grey,

With sorrow and with madness; and she dwelt,

Not in that room high on the cliff, but down,

Low down within the margin of spring tides."

And then she told me all she knew of her,

As we drove onward through the sunny day.

It was a simple tale, with few, few facts;

A life that clomb one mountain and looked forth;

Then sudden sank to a low dreary plain,

And wandered ever in the sound of waves,

Till fear and fascination overcame,

And led her trembling into life and joy.

Alas! how many such are told by night,

In fisher-cottages along the shore!

Farewell, old summer-day; I lay you by,

To tell my story, and the thoughts that rise

Within a heart that never dared believe

A life was at the mercy of a sea.

THE STORY.

Aye as it listeth blows the listless wind,

Filling great sails, and bending lordly masts,

Or making billows in the green corn fields,

And hunting lazy clouds across the blue:

Now, like a vapour o'er the sunny sea,

It blows the vessel from the harbour's mouth,

Out 'mid the broken crests of seaward waves,

And hovering of long-pinioned ocean birds,

As if the white wave-spots had taken wing.

But though all space is full of spots of white,

The sailor sees the little handkerchief

That flutters still, though wet with heavy tears

Which draw it earthward from the sunny wind.

Blow, wind! draw out the cord that binds the twain,

And breaks not, though outlengthened till the maid

Can only say, I know he is not here.

Blow, wind! yet gently; gently blow, O wind!

And let love's vision slowly, gently die;

And the dim sails pass ghost-like o'er the deep,

Lingering a little o'er the vanished hull,

With a white farewell to the straining eyes.

For never more in morning's level beam,

Will the wide wings of her sea-shadowing sails

From the green-billowed east come dancing in;

Nor ever, gliding home beneath the stars,

With a faint darkness o'er the fainter sea,

Will she, the ocean-swimmer, send a cry

Of home-come sailors, that shall wake the streets

With sudden pantings of dream-scaring joy.

Blow gently, wind! blow slowly, gentle wind!

Weep not, oh maiden! tis not time to weep;

Torment not thou thyself before thy time;

The hour will come when thou wilt need thy tears

To cool the burning of thy desert brain.

Go to thy work; break into song sometimes,

To die away forgotten in the lapse

Of dreamy thought, ere natural pause ensue;

Oft in the day thy time-outspeeding heart,

Sending thy ready eye to scout the east,

Like child that wearies of her mother's pace,

And runs before, and yet perforce must wait.

The time drew nigh. Oft turning from her work,

With bare arms and uncovered head she clomb

The landward slope of the prophetic hill;

From whose green head, as on the verge of time,

Seer-like she gazed, shading her hope-rapt eyes

From the bewilderment of work-day light,

Far out on the eternity of waves;

If from the Hades of the nether world

Her prayers might draw the climbing skyey sails

Up o'er the threshold of the horizon line;

For when he came she was to be his wife,

And celebrate with rites of church and home

The apotheosis of maidenhood.

Time passed. The shadow of a fear that hung

Far off upon the horizon of her soul,

Drew near with deepening gloom and clearing form,

Till it o'erspread and filled her atmosphere,

And lost all shape, because it filled all space,

Reaching beyond the bounds of consciousness;

But ever in swift incarnations darting

Forth from its infinite a stony stare,

A blank abyss, an awful emptiness.

Ah, God! why are our souls, lone helpless seas,

Tortured with such immitigable storm?

What is this love, that now on angel wing

Sweeps us amid the stars in passionate calm;

And now with demon arms fast cincturing,

Drops us, through all gyrations of keen pain,

Down the black vortex, till the giddy whirl

Gives fainting respite to the ghastly brain?

Not these the maiden's questions. Comes he yet?

Or am I widowed ere my wedding day?

Ah! ranged along our shores, on peak or cliff,

Or stone-ribbed promontory, or pier head,

Maidens have aye been standing; the same pain

Deadening the heart-throb; the same gathering mist

Dimming the eye that would be keen as death;

The same fixed longing on the changeless face.

Over the edge he vanished--came no more:

There, as in childhood's dreams, upon that line,

Without a parapet to shield the sense,

Voidness went sheer down to oblivion:

Over that edge he vanished--came no more.

O happy those for whom the Possible

Opens its gates of madness, and becomes

The Real around them! those to whom henceforth

There is but one to-morrow, the next morn,

Their wedding day, ever one step removed;

The husband's foot ever upon the verge

Of the day's threshold; whiteness aye, and flowers,

Ready to meet him, ever in a dream!

But faith and expectation conquer still;

And so her morrow comes at last, and leads

The death-pale maiden-ghost, dazzled, confused,

Into the land whose shadows fall on ours,

And are our dreams of too deep blessedness.

May not some madness be a kind of faith?

Shall not the Possible become the Real?

Lives not the God who hath created dreams?

So stand we questioning upon the shore,

And gazing hopeful towards the Unrevealed.

Long looked the maiden, till the visible

Half vanished from her eyes; the earth had ceased

That lay behind her, and the sea was all;

Except the narrow shore, which yet gave room

For her sea-haunting feet; where solid land,

Where rocks and hills stopped, frighted, suddenly,

And earth flowed henceforth on in trembling waves,

A featureless, a half re-molten world,

Halfway to the Unseen; the Invisible

Half seen in the condensed and flowing sky

Which lay so grimly smooth before her eyes

And brain and shrinking soul; where power of man

Could never heap up moles or pyramids,

Or dig a valley in the unstable gulf

Fighting for aye to make invisible,

To swallow up, and keep her smooth blue smile

Unwrinkled and unspotted with the land;

Not all the changes on the restless wave,

Saving it from a still monotony,

Whose only utterance was a dreary song

Of stifled wailing on the shrinking shore.

Such frenzy slow invaded the poor girl.

Not hers the hovering sense of marriage bells

Tuning the air with fragrance of sweet sound;

But the low dirge that ever rose and died,

Recurring without pause or any close,

Like one verse chaunted aye in sleepless brain.

Down to the shore it drew her from the heights,

Like witch's demon-spell, that fearful moan.

She knew that somewhere in the green abyss

His body swung in curves of watery force,

Now in a circle slow revolved, and now

Swaying like wind-swung bell, when surface waves

Sank their roots deep enough to reach the waif,

Hither and thither, idly to and fro,

Wandering unheeding through the heedless sea.

A kind of fascination seized her brain,

And drew her onward to the ridgy rocks

That ran a little way into the deep,

Like questions asked of Fate by longing hearts,

Bound which the eternal ocean breaks in sighs.

Along their flats, and furrows, and jagged backs,

Out to the lonely point where the green mass

Arose and sank, heaved slow and forceful, she

Went; and recoiled in terror; ever drawn,

Ever repelled, with inward shuddering

At the great, heartless, miserable depth.

She thought the ocean lay in wait for her,

Enticing her with horror's glittering eye,

And with the hope that in an hour sure fixed

In some far century, aeons remote,

She, conscious still of love, despite the sea,

Should, in the washing of perennial waves,

Sweep o'er some stray bone, or transformed dust

Of him who loved her on this happy earth,

Known by a dreamy thrill in thawing nerves.

For so the fragments of wild songs she sung

Betokened, as she sat and watched the tide,

Till, as it slowly grew, it touched her feet;

When terror overcame--she rose and fled

Towards the shore with fear-bewildered eye;

And, stumbling on the rocks with hasty steps,

Cried, "They are coming, coming at my heels."

Perhaps like this the songs she used to wail

In the rough northern tongue of Aberdeen:--

Ye'll hae me yet, ye'll hae me yet,

Sae lang an' braid, an' never a hame!

Its nae the depth I fear a bit,

But oh, the wideness, aye the same!

The jaws[1] come up, wi' eerie bark;

Cryin' I'm creepy, cauld, an' green;

Come doon, come doon, he's lyin' stark,

Come doon an' steek his glowerin' een.

Syne wisht! they haud their weary roar,

An' slide awa', an' I grow sleepy:

Or lang, they're up aboot my door,

Yowlin', I'm cauld, an' weet, an' creepy!

O dool, dool! ye are like the tide--

Ye mak' a feint awa' to gang;

But lang awa' ye winna bide,--

An' better greet than aye think lang.

[Footnote 1: Jaws: English, breakers.]

Where'er she fled, the same voice followed her;

Whisperings innumerable of water-drops

Growing together to a giant voice;

That sometimes in hoarse, rushing undertones,

Sometimes in thunderous peals of billowy shouts,

Called after her to come, and make no stay.

From the dim mists that brooded seaward far,

And from the lonely tossings of the waves,

Where rose and fell the raving wilderness,

Voices, pursuing arms, and beckoning hands,

Reached shorewards from the shuddering mystery.

Then sometimes uplift, on a rocky peak,

A lonely form betwixt the sea and sky,

Watchers on shore beheld her fling wild arms

High o'er her head in tossings like the waves;

Then fix them, with clasped hands of prayer intense,

Forward, appealing to the bitter sea.

Then sudden from her shoulders she would tear

Her garments, one by one, and cast them far

Into the roarings of the heedless surge,

A vain oblation to the hungry waves.

Such she did mean it; and her pitying friends

Clothed her in vain--their gifts did bribe the sea.

But such a fire was burning in her brain,

The cold wind lapped her, and the sleet-like spray

Flashed, all unheeded, on her tawny skin.

As oft she brought her food and flung it far,

Reserving scarce a morsel for her need--

Flung it--with naked arms, and streaming hair

Floating like sea-weed on the tide of wind,

Coal-black and lustreless--to feed the sea.

But after each poor sacrifice, despair,

Like the returning wave that bore it far,

Rushed surging back upon her sickening heart;

While evermore she moaned, low-voiced, between--

Half-muttered and half-moaned: "Ye'll hae me yet;

Ye'll ne'er be saired, till ye hae ta'en mysel'."

And as the night grew thick upon the sea,

Quenching it all, except its voice of storm;

Blotting it from the region of the eye,

Though still it tossed within the haunted brain,

Entering by the portals of the ears,--

She step by step withdrew; like dreaming man,

Who, power of motion all but paralysed,

With an eternity of slowness, drags

His earth-bound, lead-like, irresponsive feet

Back from a living corpse's staring eyes;

Till on the narrow beach she turned her round.

Then, clothed in all the might of the Unseen,

Terror grew ghostly; and she shrieked and fled

Up to the battered base of the old tower,

And round the rock, and through the arched gap,

Cleaving the blackness of the vault within;

Then sank upon the sand, and gasped, and raved.

This was her secret chamber, this her place

Of refuge from the outstretched demon-deep,

All eye and voice for her, Argus more dread

Than he with hundred lidless watching orbs.

There, cowering in a nook, she sat all night,

Her eyes fixed on the entrance of the cave,

Through which a pale light shimmered from the sea,

Until she slept, and saw the sea in dreams.

Except in stormy nights, when all was dark,

And the wild tempest swept with slanting wing

Against her refuge; and the heavy spray

Shot through the doorway serpentine cold arms

To seize the fore-doomed morsel of the sea:

Then she slept never; and she would have died,

But that she evermore was stung to life

By new sea-terrors. Sometimes the sea-gull

With clanging pinions darted through the arch,

And flapped them round her face; sometimes a wave,

If tides were high and winds from off the sea,

Rushed through the door, and in its watery mesh

Clasped her waist-high, then out again to sea!

Out to the devilish laughter and the fog!

While she clung screaming to the bare rock-wall;

Then sat unmoving, till the low grey dawn

Grew on the misty dance of spouting waves,

That mixed the grey with white; picture one-hued,

Seen in the framework of the arched door:

Then the old fascination drew her out,

Till, wrapt in misty spray, moveless she stood

Upon the border of the dawning sea.

And yet she had a chamber in her soul,

The innermost of all, a quiet place;

But which she could not enter for the love

That kept her out for ever in the storm.

Could she have entered, all had been as still

As summer evening, or a mother's arms;

And she had found her lost love sleeping there.

Thou too hast such a chamber, quiet place,

Where God is waiting for thee. Is it gain,

Or the confused murmur of the sea

Of human voices on the rocks of fame,

That will not let thee enter? Is it care

For the provision of the unborn day,

As if thou wert a God that must foresee,

Lest his great sun should chance forget to rise?

Or pride that thou art some one in the world,

And men must bow before thee? Oh! go mad

For love of some one lost; for some old voice

Which first thou madest sing, and after sob;

Some heart thou foundest rich, and leftest bare,

Choking its well of faith with thy false deeds;

Not like thy God, who keeps the better wine

Until the last, and, if He giveth grief,

Giveth it first, and ends the tale with joy.

Madness is nearer God than thou: go mad,

And be ennobled far above thyself.

Her brain was ill, her heart was well: she loved.

It was the unbroken cord between the twain

That drew her ever to the ocean marge;

Though to her feverous phantasy, unfit,

'Mid the tumultuous brood of shapes distort,

To see one simple form, it was the fear

Of fixed destiny, unavoidable,

And not the longing for the well-known face,

That drew her, drew her to the urgent sea.

Better to die, better to rave for love,

Than to recover with sick sneering heart.

Or, if that thou art noble, in some hour,

Maddened with thoughts of that which could not be,

Thou mightst have yielded to the burning wind,

That swept in tempest through thy scorching brain,

And rushed into the thick cold night of the earth,

And clamoured to the waves and beat the rocks;

And never found the way back to the seat

Of conscious rule, and power to bear thy pain;

But God had made thee stronger to endure

For other ends, beyond thy present choice:

Wilt thou not own her story a fit theme

For poet's tale? in her most frantic mood,

Not call the maniac sister, tenderly?

For she went mad for love and not for gold.

And in the faded form, whose eyes, like suns

Too fierce for freshness and for dewy bloom,

Have parched and paled the hues of tender spring,

Cannot thy love unmask a youthful shape

Deformed by tempests of the soul and sea,

Fit to remind thee of a story old

Which God has in his keeping--of thyself?

But God forgets not men because they sleep.

The darkness lasts all night and clears the eyes;

Then comes the morning and the joy of light.

O surely madness hideth not from Him;

Nor doth a soul cease to be beautiful

In His sight, when its beauty is withdrawn,

And hid by pale eclipse from human eyes.

Surely as snow is friendly to the spring,

A madness may be friendly to the soul,

And shield it from a more enduring loss,

From the ice-spears of a heart-reaching frost.

So, after years, the winter of her life,

Came the sure spring to her men had forgot,

Closing the rent links of the social chain,

And leaving her outside their charmed ring.

Into the chill wind and the howling night,

God sent out for her, and she entered in

Where there was no more sea. What messengers

Ran from the door of love-contented heaven,

To lead her towards the real ideal home?

The sea, her terror, and the wintry wind.

For, on a morn of sunshine, while the wind

Yet blew, and heaved yet the billowy sea

With memories of the night of deep unrest,

They found her in a basin of the rocks,

Which, buried in a firmament of sea

When ocean winds heap up the tidal waves,

Yet, in the respiration of the surge,

Lifts clear its edge of rock, full to the brim

With deep, clear, resting water, plentiful.

There, in the blessedness of sleep, which God

Gives his beloved, she lay drowned and still.

O life of love, conquered at last by fate!

O life raised from the dead by Saviour Death!

O love unconquered and invincible!

The sea had cooled the burning of that brain;

Had laid to rest those limbs so fever-tense,

That scarce relaxed in sleep; and now she lies

Sleeping the sleep that follows after pain.

'Twas one night more of agony and fear,

Of shrinking from the onset of the sea;

One cry of desolation, when her fear

Became a fact, and then,--God knows the rest.

O cure of all our miseries--God knows!

O thou whose feet tread ever the wet sands

And howling rocks along the wearing shore,

Roaming the confines of the endless sea!

Strain not thine eyes across, bedimmed with tears;

No sail comes back across that tender line.

Turn thee unto thy work, let God alone;

He will do his part. Then across the waves

Will float faint whispers from the better land,

Veiled in the dust of waters we call storms,

To thine averted ears. Do thou thy work,

And thou shalt follow; follow, and find thine own.

O thou who liv'st in fear of the To come!

Around whose house the storm of terror breaks

All night; to whose love-sharpened ear, all day,

The Invisible is calling at thy door,

To render up that which thou can'st not keep,

Be it a life or love! Open thy door,

And carry forth thy dead unto the marge

Of the great sea; bear it into the flood,

Braving the cold that creepeth to thy heart,

And lay thy coffin as an ark of hope

Upon the billows of the infinite sea.

Give God thy dead to keep: so float it back,

With sighs and prayers to waft it through the dark,

Back to the spring of life. Say--"It is dead,

But thou, the life of life, art yet alive,

And thou can'st give the dead its dear old life,

With new abundance perfecting the old.

God, see my sadness; feel it in thyself."

Ah God! the earth is full of cries and moans,

And dull despair, that neither moans nor cries;

Thousands of hearts are waiting the last day,

For what they know not, but with hope of change,

Of resurrection, or of dreamless death.

Raise thou the buried dead of springs gone by

In maidens' bosoms; raise the autumn fruits

Of old men feebly mournful o'er the life

Which scarce hath memory but the mournfulness.

There is no Past with thee: bring back once more

The summer eves of lovers, over which

The wintry wind that raveth through the world

Heaps wretched leaves, half tombed in ghastly snow;

Bring back the mother-heaven of orphans lone,

The brother's and the sister's faithfulness;

Bring forth the kingdom of the Son of Man.

They troop around me, children wildly crying;

Women with faded eyes, all spent of tears;

Men who have lived for love, yet lived alone;

And worse than so, whose grief cannot be said.

O God, thou hast a work to do indeed

To save these hearts of thine with full content,

Except thou give them Lethe's stream to drink,

And that, my God, were all unworthy thee.

Dome up, O Heaven! yet higher o'er my head;

Back, back, horizon! widen out my world;

Rush in, O infinite sea of the Unknown!

For, though he slay me, I will trust in God.

A Story Of The Sea-shore

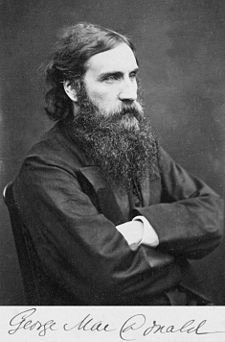

George Macdonald

(1)

Poem topics: angel, autumn, away, beauty, believe, brother, change, childhood, children, dance, destiny, fairy, father, feel, fire, fog, food, freedom, hunting, husband, Print This Poem , Rhyme Scheme

Submit Spanish Translation

Submit German Translation

Submit French Translation

<< Translations. - The Hundred And Twenty-fourth Psalm. (luther's Song-book.) Poem

A Song-sermon: Poem>>

Write your comment about A Story Of The Sea-shore poem by George Macdonald

Best Poems of George Macdonald